Anatomy of Survival

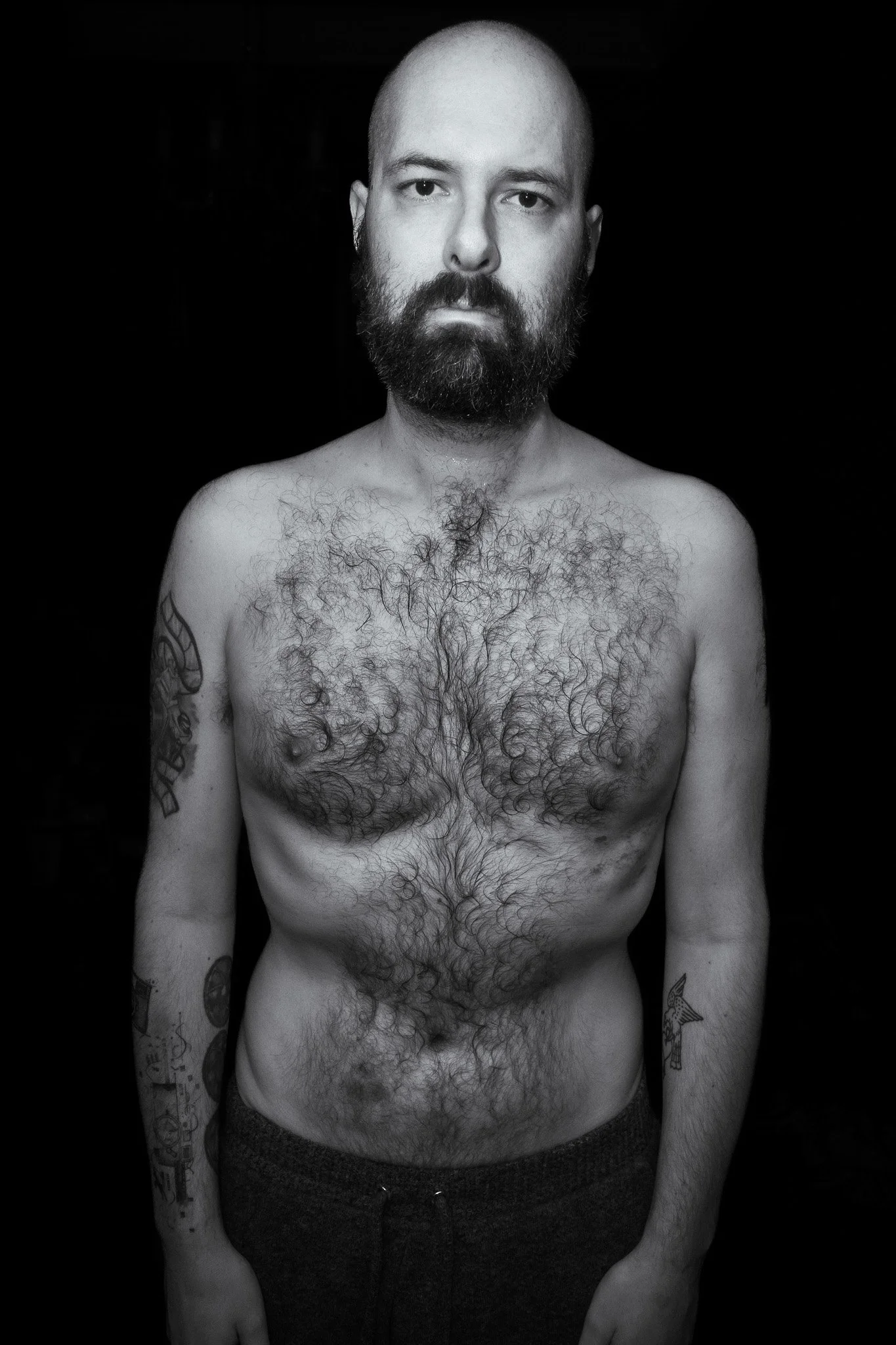

Illness demands a different kind of truth. Before ulcerative colitis, I understood my body as a tool — something dependable, invisible, taken for granted. But chronic illness has a way of stripping life back to its raw mechanics: blood counts, sleepless nights, chemical drips, the quiet authority of nurses, and the slow betrayal of your own organs. Anatomy of Survival is my attempt to look closely at what happened to me — not to sensationalise the trauma, but to understand it, record it, and reclaim it.

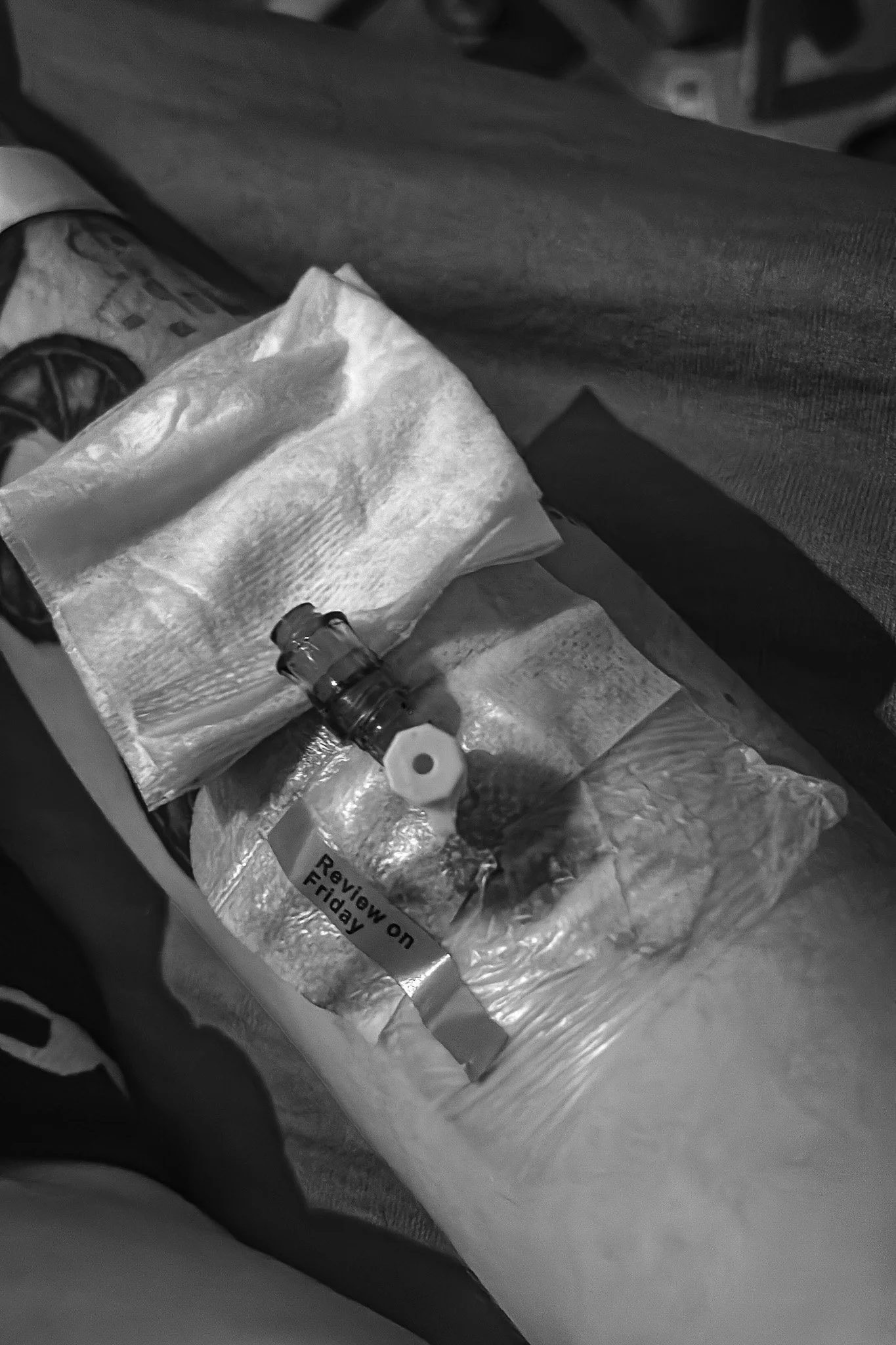

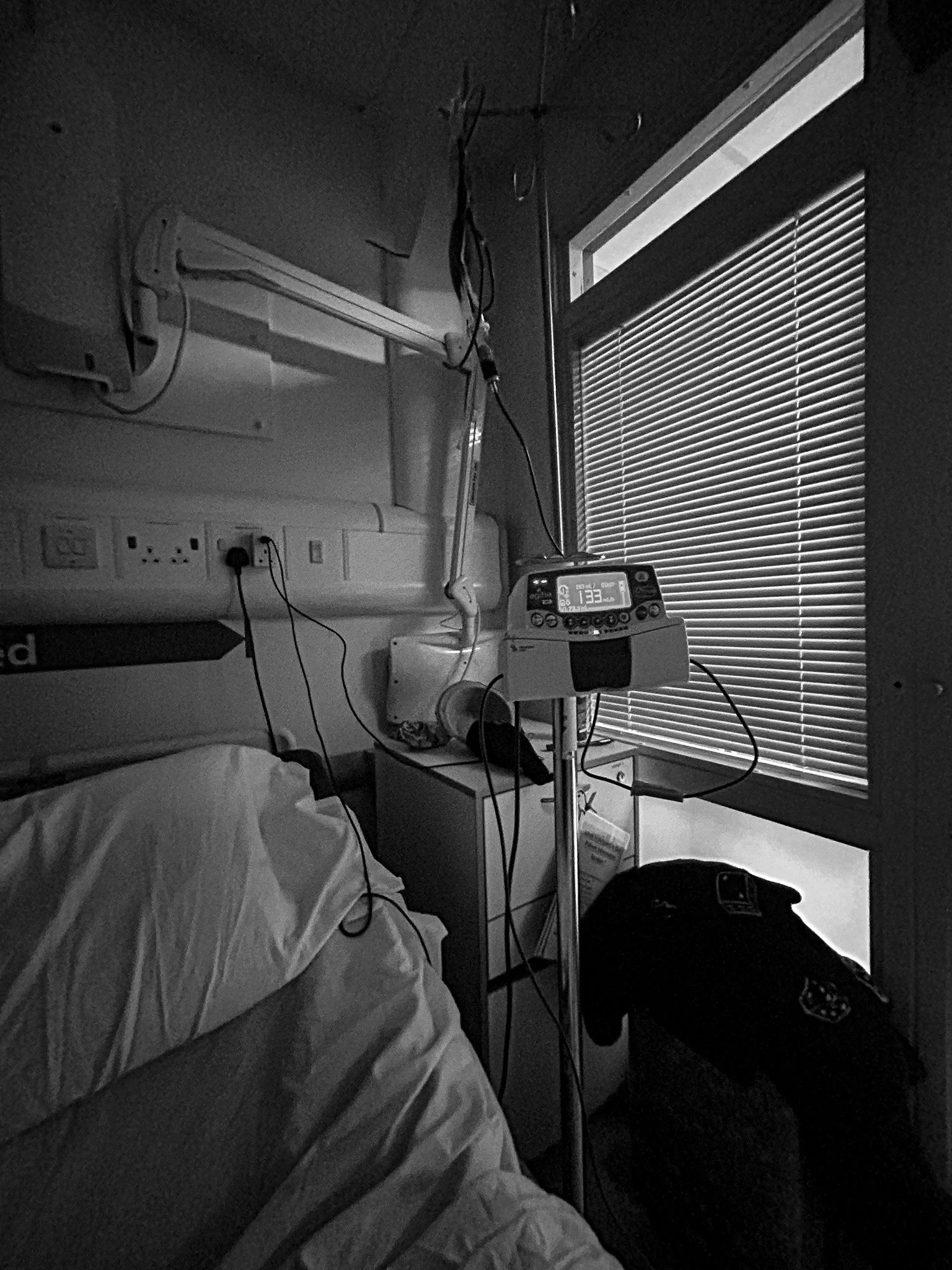

This work began not in a moment of clarity, but in collapse. As the illness worsened, my world narrowed to hospital beds, fluorescent wards, plastic trays and medical routines that carved through the days. Photography became a lifeline — at first as distraction, then as documentation, and finally as confrontation. It was a way to witness myself from the outside when everything inside was chaos. The camera let me study what I was enduring when language began to fail: the dressing, the stoma, the scars, the objects that stood between life and loss.

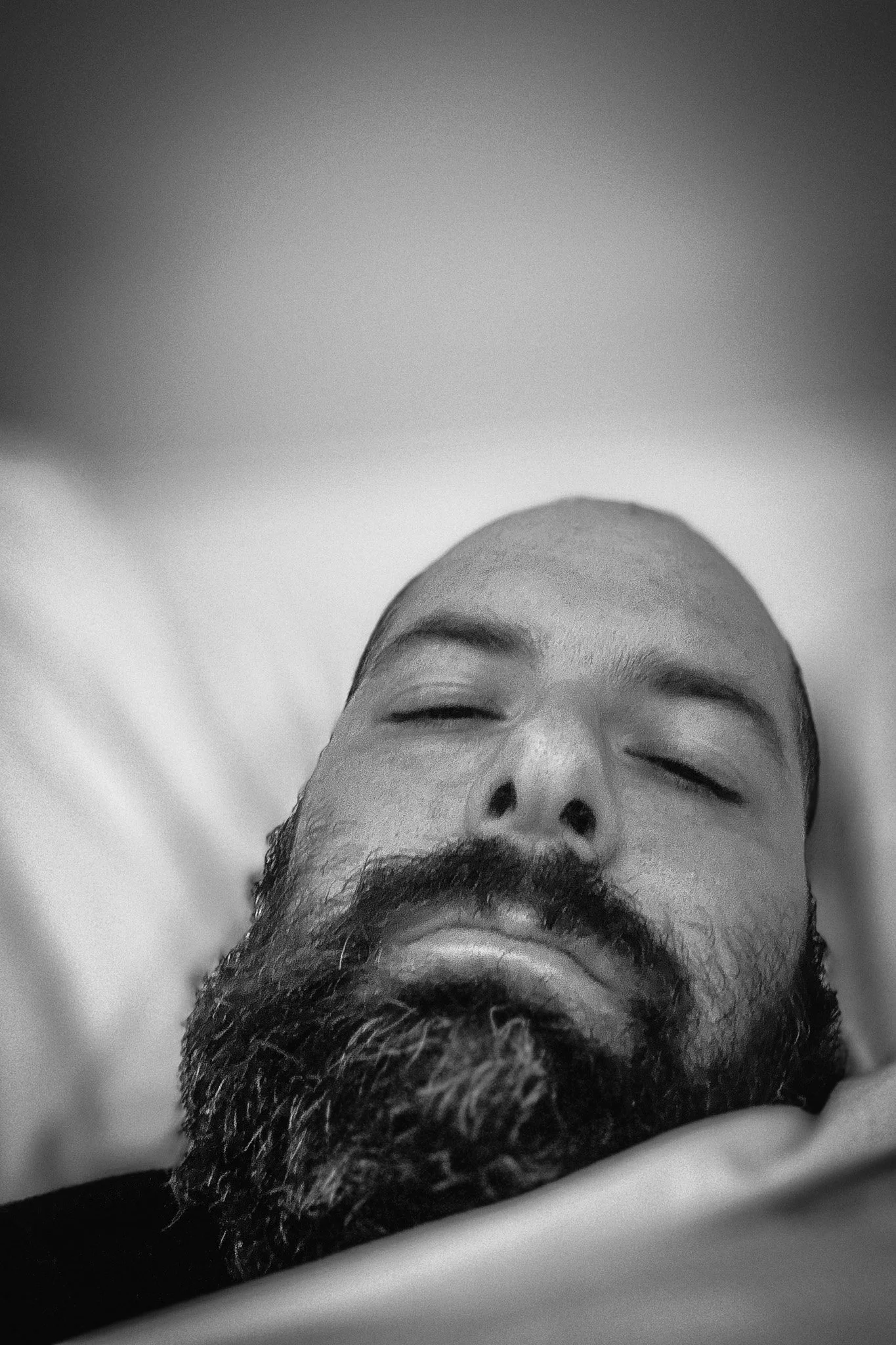

Surgery brought both violence and relief. To live, my body would have to be opened, altered, re-routed — a map redrawn without consultation. I woke to a new anatomy, stitched and swollen, with a stoma bag fixed to my abdomen and a future I no longer recognised. These images sit in the aftermath of that moment. They explore the physical realities of survival — the tubes, the tools, the wound — alongside the quieter psychological terrain: shame, exhaustion, gratitude, and the delicate work of accepting a body that has changed without permission.

Anatomy of Survival is not a linear story. Illness does not move in clean narrative arcs. Instead, the work is structured in themes — the clinical world that holds you, the body as evidence, the spaces of waiting, and the daily rituals that make endurance possible. Within these fragments is a simple truth: healing is not fast, and survival is not heroic. It is often slow, repetitive, undramatic — measured in appointments, dressings, and days endured rather than days celebrated.

I share this work because so much of chronic illness is hidden. We are encouraged to speak only once we are “better,” as though vulnerability must earn its right to be seen. But there is value in the uncomfortable middle — in the images made between collapse and recovery — where the body is learning how to continue. If these photographs hold anything, I hope they hold honesty. Not triumph or tragedy, but the complexity of being changed and choosing to live on.

This is the anatomy of my survival: unclean, imperfect, marked, and ongoing. It is a record of pain, but also of persistence. Of the body that failed, and the body that stayed.